Zaman – Intermediate microeconomics introduction

By Asad Zaman

Comments on Varian: Intermediate Microeconomics. Chapter 1

Hal R. Varian, Intermediate Microeconomics: A Modern Approach, 9th Edition, W W Norton & Co. New York London, 2014.

Brief Summary of Post:

These comments are about the first few pages of the chapter. Quotes from Varian are in italics. Criticisms are made in this post about the concepts of models, optimization, equilibrium, and the concept of exogeneity, as dealt with by Varian. Models are used without explicit discussion of the relationships between model and reality, which is essential to understanding how models work. For an extended discussion see my lecture on Models Versus Reality. The post explains why optimization, taken as “tautological” by Varian, is false as a description of consumer behavior. It also explains the rhetorical strategy used to deceive students into thinking of this assumption as “tautological”. For an extended discussion of the conflict between axiomatic theory of consumer behavior and actual human behavior, see my short post on: Behavioral vs Neoclassical Economics, which also has links to more extensive discussions. We also discuss how confusion about the concept of exogeneity causes difficulties with the supply and demand model under discussion in this chapter of Varian. Similarly, the decision to study only equilibrium behavior handicaps economists, making them blind to disequilibrium events like the Global Financial Crisis.

Extended Discussion:

To explain supply and demand, Varian starts by constructing a model for understanding the prices of apartments. We create a model by simplifying the world that we see, to highlight those elements that consider important. At the same time, we suppress elements that we think do not matter. This decision, what we choose to model, and what we choose to ignore, is of extreme importance, but completely hidden from view. For example, suppose we believe (as I do) that human welfare is strongly dependent on communities in which humans live. Then in studying housing, I would keep the impacts of housing choices on communities as a crucial variable which we must model. Then I would be looking at groups of people living together in nearby houses as a community. However, these issues would be completely ignored by people who believe in individualism, where everyone leads isolated and lonely lives independently of any community. There is a strong element of subjectivity and hidden social norms in the process of modeling, carried out under the pretense of objectivity.

We will think of the apartments as being located in two large rings surrounding the University. The adjacent apartments are in the inner ring, while the rest are located in the outer ring. We will focus exclusively on the market for apartments in the inner ring. The outer ring should be interpreted as where people can go who don’t find one of the closer apartments. We’ll suppose that there are many apartments available in the outer ring, and their price is fixed at some known level. We’ll be concerned solely with the determination of the price of the inner-ring apartments and who gets to live there. (p.2)

There are two rings – why? The outer ring accommodates those people who cannot find an apartment within the market we will study. This is a PARTIAL EQUILIBRIUM model – that is we study one aspect in isolation, without worrying about what happens outside this model.

An economist would describe the distinction between the prices of the two kinds of apartments in this model by saying that the price of the outer-ring apartments is an exogenous variable, while the price of the inner-ring apartments is an endogenous variable. This means that the price of the outer-ring apartments is taken as determined by factors not discussed in this particular model, while the price of the inner-ring apartments is determined by forces described in the model. (p.2)

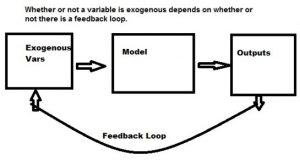

“the price of outer ring apartments is determined by factors not discussed in this model.” This is an OSTRICH’s definition of exogeneity. It means that we can make variables exogenous by not discussing them. An exogenous variable MUST NOT BE INFLUENCED by endogenous variables. This is not mentioned in the definition above, because exogeneity concepts are not well understood by most economists. To ensure that a variable is exogenous, it is necessary to prove that there are no feedback loops, as described in the diagram below. Of course, it is understood that models are only approximations, and weak feedback loops may be ignored. However, completely ignoring the issue leads to widespread misunderstandings; these misunderstandings are embedded within the standard supply and demand model being exposited by Varian. Once we achieve clarity on the issue of exogeneity and endogeneity, we can see clearly that supply and demand cannot function in the way that is described in economic textbooks. This will be explained in greater detail in a later post dedicated to this issue.

Varian’s confusion about exogeneity (that it can be achieved by refusing to discuss a variable) is extremely important in the context of the supply and demand model under discussion in this chapter– one cannot contemplate variations in an endogenous variable (because endogenous variables are not free to move; they can only change if some of the exogenous variables which affect them change). This means that asking what consumers will demand if the price changes is a WRONG question — prices are endogenous and they cannot change by themselves. An increase in price caused by shortfall in supply would lead different consequences from an increase in price caused by an upward shift in the demand. If a consumer is asked what he will do when the price changes, he should ask WHY did the price change, because his response to the price change DEPENDS on cause of the price change. He cannot provide a response to the question without learning about the cause, and whether or not this is a temporary or permanent change. For more details on this issue, see Saglam & Zaman .

But what determines this price? What determines who will live in the inner-ring apartments and who will live farther out? What can be said about the desirability of different economic mechanisms for allocating apartments? What concepts can we use to judge the merit of different assignments of apartments to individuals? These are all questions that we want our model to address (p2)

Note that judgement of merit automatically involves NORMATIVE judgments. Also, the mechanisms under discussion are based on social norms which legitimize certain concepts of private property, implicitly, in background, and without discussion. These norms are then taken as objective facts. This practice of concealing norms in the framework of discussion, and then pretending that economics is a positive theory, is widespread throughout economics; see my paper on the Normative Foundations of Scarcity. The questions that the model is used to study is PARTLY a consequence of how we choose to model, and partly determined by the model. This will be seen more clearly later, when we look at alternative ways to model the same economic situation described by Varian. Now Varian introduces what might be called the fundamental methodological commitment made by modern economic theory:

The optimization principle: People try to choose the best patterns of consumption that they can afford.

(This) is almost tautological. If people are free to choose their actions, it is reasonable to assume that they try to choose things they want rather than things they don’t want. Of course there are exceptions to this general principle, but they typically lie outside the domain of economic behavior.(p3)

Far from being tautological as Varian states, this is simply not true. It might have been true if consumption was a central or main concern of life. However, if our main interest lies elsewhere, then we would do SATISFICING – that is, consume whatever is sufficient for our needs, instead of MAXIMIZING consumption – undertaking the time and effort to find the best possible combination of consumer goods which will yield us the maximum pleasure. By satisficing, we can fulfill our needs and save time, money, and mental energy for pursuit of higher goals of life. If consumption is the highest goal of life (and a market economy creates this illusion and orientation) than the above optimization principle MIGHT hold. In real life, behavioral economists and psychologists have tested this theory, and found that it fails – people do not try to choose the best patterns of consumption that they can afford. Advertising OFTEN misleads people into buying products that they do not want, that they cannot afford, and that they do not use. One study in Australia showed that every year people purchase more than 10.5 billion dollars’ worth of goods that they never use. So obviously, it is not true that people optimize their consumption patterns. Interestingly, a robust finding replicated globally and in many different fields of study, is that while consumption brings short term pleasure, long run happiness is more tied to generosity, sacrificing short term personal goals for higher long run goals – for example, dieting and exercise reduce utility in short run, but create long run benefits. Once this is taken into consideration, even the concept of maximization becomes ambiguous – are we talking long run, or short run, since there is conflict between these two?

It is very important to understand the rhetorical strategy being used by Varian, to convince students of the truth of a theory which is manifestly false. To a first approximation, it is useful to classify truths as being of two types: analytic and synthetic. The analytic truths, also called tautologies, are those where axioms are used to logically derive results, like 2+2=4 or the Pythagorean Theorem. These are true without any reference to real world observations. Synthetic truths are truths about the real world, based on observations. When we talk about human behavior in the realm of consumption, to arrive at a synthetic truth, it is necessary to produce a vast collection of observations, to justify a generalization. This is the standard induction principle of Baconian science, where by observing a particular pattern of regular occurrences, we deduce a law that this pattern necessarily holds. In order to study modern microeconomics, we must scrupulously avoid discussing actual human behavior, which is in violent conflict with axioms of economic theory that Varian will introduce later. Therefore, it is essential for Varian to convert a synthetic truth – a statement about human behavior as a consumer – into an analytic truth, a logical truth which is true by definition. Then he can assert that the economic theory of consumer behavior is a tautology, a logical truth which does not require confirmation by looking at actual human behavior. We now explain how this sleight-of-hand is accomplished.

As stated by Varian, the optimization principle is too ambiguous to be meaningful – what is “best” and what does it mean to say “that they can afford”? By being flexible in interpretation, one can stretch the meaning sufficiently so that it might become true. In the context of justification, the statement is interpreted flexibly, so that it seems “almost tautological”. When interpreted like this, it is a statement about “goal-driven” behavior – every individual is driven by goals, and he chooses consumption bundles to achieve these goals. At this level, it appears harmless, though one might doubt if it would apply to a Buddhist ascetic who has renounced the world. However, in the context of application economists (including Varian) transform this general principle of goal driven behavior into a narrow and special principle which specifies the goal as being utility maximization and the “affordability” as being the budget constraints. This translation introduces many hidden assumptions about human behavior without any discussion, under the disguise of a “tautology”. The utility function depends only on your own consumption, assuming without discussion, that we do not care anything about others – a manifestly false assumption. Textbooks on Consumer Behavior taught in the Business school often discuss and reject the economists’ theories. These textbooks are based on empirical studies of consumer behavior, and show that the economists’ models do not even come close to describing the complex reality of consumer behavior.

The second principle introduced by Varian is also part of the core methodological commitments of modern economic theory:

The equilibrium principle: Prices adjust until the amount that people demand of something is equal to the amount that is supplied.

The second notion is a bit more problematic. It is at least conceivable that at any given time peoples’ demands and supplies are not compatible, and hence something must be changing. These changes may take a long time to work themselves out, and, even worse, they may induce other changes that might “destabilize” the whole system. This kind of thing can happen . . . but it usually doesn’t. In the case of apartments, we typically see a fairly stable rental price from month to month. It is this equilibrium price that we are interested in, not in how the market gets to this equilibrium or how it might change over long periods of time. (p3)

This principle is completely wrong. In recessions, it is a common experience that vast numbers of people apply for a few positions available. Obviously this shows an excess supply of labor, so the price should be adjusted downward. However, in many historical episodes all over the globe, even though this pattern persisted for more than a decade, there was no downward adjustment in the real wage for labor – they remained more or less stable and flat. Similarly, in many markets, one observes excess supply and also excess demand, but one does not see any adjustment in prices. That is why STICKY price models have become popular in some parts of economics. Basically it was this observation – that wages did not adjust downwards even though there was excess supply of labor – that led Keynes to the creation of Keynesian economics. The MAIN PURPOSE of Keynesian economics was to explain WHY supply and demand theory does not work in the labor market.

The second part of Varian’s explanation for why we study equilibrium is even worse: “It is this equilibrium price that we are interested in, not in how the market gets to this equilibrium or how it might change over long periods of time” Who decided that this is what we are interested in? In the Global Financial Crisis, we were interested in finding out why the prices of homes collapsed suddenly, in violation of equilibrium theory. Economists who are not interested in this will never be able to answer this question. That is why the Queen of England went to the London School of Economics to ask “Why did no one see this coming?” There are many strong objections to the idea that we should only be interested in equilibrium, and not in how the market gets to equilibrium. General Equilibrium models, Game Theoretic Models, Rational Expectations models, and many others, ubiquitously have multiple equilibria. This means that we cannot learn which among the many equilibria will emerge unless we study the process by which markets reach equilibrium. In fact, such studies show that in most markets, equilibrium is never achieved. Different equilibria can act as attractors or as repellers in a dynamic process, which is usually path dependent and time irreversible. So to understand real economies, we must go beyond equilibria and study both historical context and the particular forces which drive towards one equilibrium over others, or possibly cause cyclical and oscillating behavior known as business cycles. Unfortunately, as Varian writes, economists are ONLY interested in the equilibrium price, so they completely fail to understand the real world, and in particular the global financial crisis, where disequilibrium is the rule, rather than the exception.

Commentary added 16th March 2017