Birks – Mankiw 7th edn Chapter 30: Money Growth and Inflation

Mankiw, N. G. (2015) Principles of economics (7th ed.) Ch.30

Principles of macroeconomics (7th ed.) Ch.17

Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning

Money Growth and Inflation

When reading the chapter, here are some aspects to consider:

1. A standard approach to analysis is to begin with a simple model with restrictive assumptions. These assumptions can then be relaxed later. For example, the money supply curve may not be vertical and money supply may not be (in reality it is not) fully determined by government.

2. On the neutrality of money, short-run effects may have long-run implications (see hysteresis). For example, periods of unemployment may affect the future productivity of the labour force. Low demand may reduce investment and hence the size and age of capital stock. This suggests that there may be path dependence (as when future options are affected by past decisions), although this may not be picked up by static analysis.

3. There may be additional factors to consider in relation to the neutrality of money, given Japan’s experience. This is taken from an article dated 18 April 2013:

“This month the Bank of Japan endorsed more monetary easing, announcing plans to purchase 7.5 trillion yen ($76.5 million) of bonds and double the country’s monetary base over two years.

In his speech today, Miyao said inflation would indeed reach that 2 percent target, and fairly soon.”

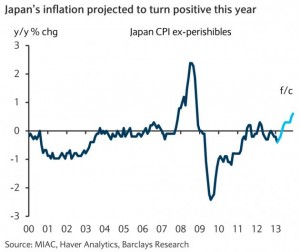

Japan has experienced persistent deflation, as indicated by this graph, taken from here:

The policy may have succeeded, according to an account here: “The inflation rate in Japan was recorded at 1.50 percent in February of 2014.”

4. We should be careful about seeing a textbook model as an accurate representation of the real world. Here is a quote (slightly modified) from a video statement by Richard Koo, Chief Economist of Nomura Research Institute:

“Most growth is happening in Asia, when the rest of the world is doing poorly. So if this area doesn’t move forward, those of us who live in the developed world will be suffering even more. I think the fact that private sectors in all of these economies in the developed world are saving money at zero interest rates, we are completely outside the textbook world. The private sector is not supposed to save at zero interest rate, but when you look at the numbers, it is outrageous how much people are saving, which is why the economies are doing so poorly. We need ideas to overcome this, or at least to understand why it is happening, and what we can do about it.”

And here is an extract from the appearance of Alan Greenspan, former chairman of the US Federal Reserve, before the House Oversight and Government Affairs Committee in 2008. Rep. Henry Waxman chaired the committee:

“GREENSPAN: Well remember…an ideology is…a conceptual framework…the way people deal

with reality. Everyone has one. To exist, you need an ideology. The question is whether it is

accurate or not. And what I’m saying to you is yes, I’ve found a flaw…

WAXMAN: You found a flaw in the reality…

GREENSPAN: Flaw in the model that I perceived as the critical functioning structure that defines

how the world works.

WAXMAN: In other words, you found that your view of the world, your ideology was not right.

GREENSPAN: Precisely.”

James, F. (2008, 23 October). Greenspan: Money mess rocked his world.

5. The Quantity Theory of Money is based on an earlier identity, M x V = P x T, where T represents transactions and the other variables have the same meaning as given in your text. In this form it states that the amount of money paid for goods and services is equal to the monetary value of all goods and services given in transactions. Hence, it is always true. The substitution of Y for T requires a redefinition of V. It can no longer be the number of times a unit of currency is used in a period. Remember from the simple circular flow diagram that the flow of goods and services from firms to households is matched by a flow of money in the other direction. This is represented by M x V = P x Y. There is also a flow of factor services (labour, etc.) from households to firms, and factor payments (wages, etc.) in the reverse direction. In addition, production can involve many intermediate transactions (see “intermediate good” in Mankiw Chapter 23, Measuring a Nation’s Income, section 2c).

6. When looking at graphs showing relationships between two variables, note that a relationship can be observed between any variables which follow a trend through time. This may not be causal, and if it is causal, there are questions about the direction of causality (which could be one-way, or in both directions if there is feedback).

7. The graphs in Figure 4 are described using the term “consistent with”. As Milton Friedman has pointed out, if one explanation is consistent with a set of facts, there may be many other explanations which are also consistent with those facts. (“Observed facts are necessarily finite in number; possible hypotheses, infinite. If there is one hypothesis that is consistent with the available evidence, there are always an infinite number that are.”)

8. We should note not only possible costs of deflation, but also potential costs of controlling inflation.

9. The explanation of the Wizard of Oz that Mankiw gives has been challenged. See Hansen, B. A. (2002). The Fable of the Allegory: The Wizard of Oz in Economics. The Journal of Economic Education, 33(3), 254-264.

Commentary by Stuart Birks, 2 September 2014