American Myth

Download the WEA commentaries issue ›

By David Ruccio

One of the most pernicious myths in the United States is that higher education successfully levels the playing field across students with different backgrounds and therefore reduces wealth inequality and represents the solution to job losses.

The reality is quite different—for the population as a whole and, especially, for racial and ethnic minorities.

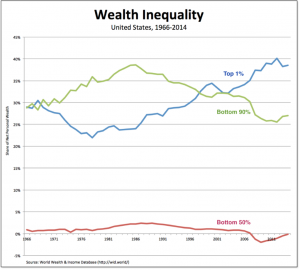

As is clear from the chart above, the share of wealth owned by the top 1 percent has risen dramatically since the mid-1970s, rising from 22.9 percent in 1976 to 38.6 percent in 2014. Meanwhile, the share owned by the bottom 90 percent has declined, falling from 34.2 percent to 27 percent. And that of the bottom 50 percent? It has remained virtually unchanged at a negligible amount, falling from 0.9 percent to zero.

During that same period, according to the U.S. Census Bureau (pdf), the proportion of Americans aged 25 to 29 with a bachelor’s degree or higher rose from 24 percent to 36 percent. (For the entire population 25 and older, the percentage with that level of education rose from 15 to 33.)

So, no, higher education has not leveled the playing field or reduced wealth inequality. In fact, it seems, quite the opposite appears to be the case.

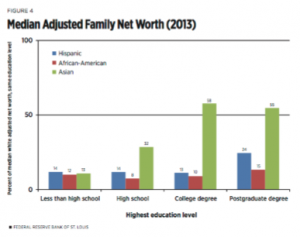

And that’s true, too, for racial and ethnic disparities in wealth. As William R. Emmons and Lowell R. Ricketts (pdf) of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis have concluded:

Despite generations of generally rising college-graduation rates, higher education’s promise of significantly reducing income and wealth disparities across all races and ethnicities remains largely unfulfilled. . .rather than promoting economic equality across all races and ethnicities, higher education unintentionally has become an engine for growing disparities.

Thus, for example, median Hispanic and black wealth levels decline relative to similarly educated whites as education increases until the very top. Moreover, only about 7 percent of black families and 5 percent of Hispanic families have postgraduate degrees, and wealth disparities remain large even there.

Darrick Hamilton and William A. Darity, Jr. (pdf), who participated in the same symposium, go even further. According to them, the United States has a fundamental problem in discussing wealth disparities according to race and ethnicity:

Much of the framing around wealth disparity, including the use of alternative financial service products, focuses on the poor financial choices and decisionmaking on the part of largely Black, Latino, and poor borrowers, which is often tied to a culture of poverty thesis regarding an undervaluing and low acquisition of education.

Thus, while they agree that a college degree is positively associated with wealth within racial and ethnic groups, it is still the case that it does little to address the massive wealth gap across such groups.

We’re also learning that another part of the American myth, encouraging young people to attend college to compensate for the loss of jobs, doesn’t work either. In fact, when states suffer a widespread loss of jobs, the damage extends to the next generation, where college attendance drops among the poorest students.

That’s the conclusion of new research Elizabeth O. Ananat and her coauthors, just published in Science (unfortunately behind a paywall). What they found is that

local job losses can both worsen adolescent mental health and lower academic performance and, thus, can increase income inequality in college attendance, particularly among African-American students and those from the poorest families.

Their argument is that macro-level job losses are best understood as “community-level traumas” that negatively affect the learning ability and the mental health not only of young people who experience job loss within their own families, but also of the other children in states where the destruction of jobs is widespread.

So, the problem of job losses can’t be solved by workers sending their children to college in search of jobs in the “new economy.” Nor is the predicament confined to the white working-class. In fact, the effects of job losses are similar, but even worse, among African-American youth.

That’s why Ananat argues that

white working class people and African-American working class people are in the same boat due to job destruction. Imagine the policies we could have if folks found common ground over that.

And, I would add, those policies need to go beyond the “active labor market policies”—such as “rigorous job training and active matching of worker skills to employer needs”—the authors, along with mainstream economists and politicians, put forward.*

And yet the myth persists. American elites and policymakers still to choose to emphasize the economic returns to education as the panacea to address socially established wealth disparities, structural barriers of racial and ethnic economic inclusion, and the negative consequences of job losses.

The question is, why?

According to Hamilton and Darity, such a view

follows from a neoliberal perspective, where the free market, as long as individual agents are properly incentivized, is supposed to be the solution to all our problems, economic or otherwise. The transcendence of Barack Obama becomes the ideal symbolism and spokesperson of this political perspective. His ascendency becomes an allegory of hard work, merit, efficiency, social mobility, freedom and fairness, individual agency, and personal responsibility. The neoliberal ideology is not limited to race. It more generally places the onus on individual actions, and more broadly leads to deficiency narratives for low achievement, but this is especially the case when considering race and other stigmatized workers. Perhaps the greatest rhetorical victory of this paradigm is convincing the masses that implicit in unfettered markets is the “American Dream”—the hope that, even if your lot in life is subpar, with patience and individual hard work, you can turn your proverbial “rags into riches.”

And so the myth of college and the American Dream is perpetuated, while the obscenely unequal distribution of wealth and the devastating effects of job losses—across the entire population, and especially with respect to ethnic and racial minorities—continue unabated.

*Policies to help “disadvantaged workers, especially African Americans, Hispanics and rural residents,” also need to go beyond encouraging the Fed to keep interest-rates low. That still leaves job decisions in the hands of employers, forcing individual workers to have the freedom to chase after jobs and to send their children to college.

From: pp.3-5 of WEA Commentaries 7(3), June 2017

http://www.worldeconomicsassociation.org/files/Issue7-3.pdf

We have here the challenges of single variable causation: Hypothesis is that more education causes more income/wealth, although we can test with a Null Hypothesis if we are statistically-minded. However, I believe the author is essentially right, IF we don’t look closer at what majors are involved. I was a history-philosophy of science major at a well-known US university, & gravitated to economics in grad school to help change the world for the better. With another PhD from the UC, I have spent 40+ years as a global business business consultant/professor. Around the world I see the business winners, aside from those with connections, are those who have energy, social skills & the ability to analyze (or at least to understand others’ analyses). Since the economists bring a deficient tool kit, those who have an ability in financial analysis become winners almost always.

As I have been a Professor of International Management, specializing in tech issues, you know exactly the sort of people who I am describing as the economic winners in the global race for financial glory. With weak unions & little lifetime employment for white collar workers, I see folks as I have described–regardless of race, gender or nationality–as tending to economic success. Notice the number of East Indians in Computer Science, & the number of Asians of all nationalities in Engineering as examples.